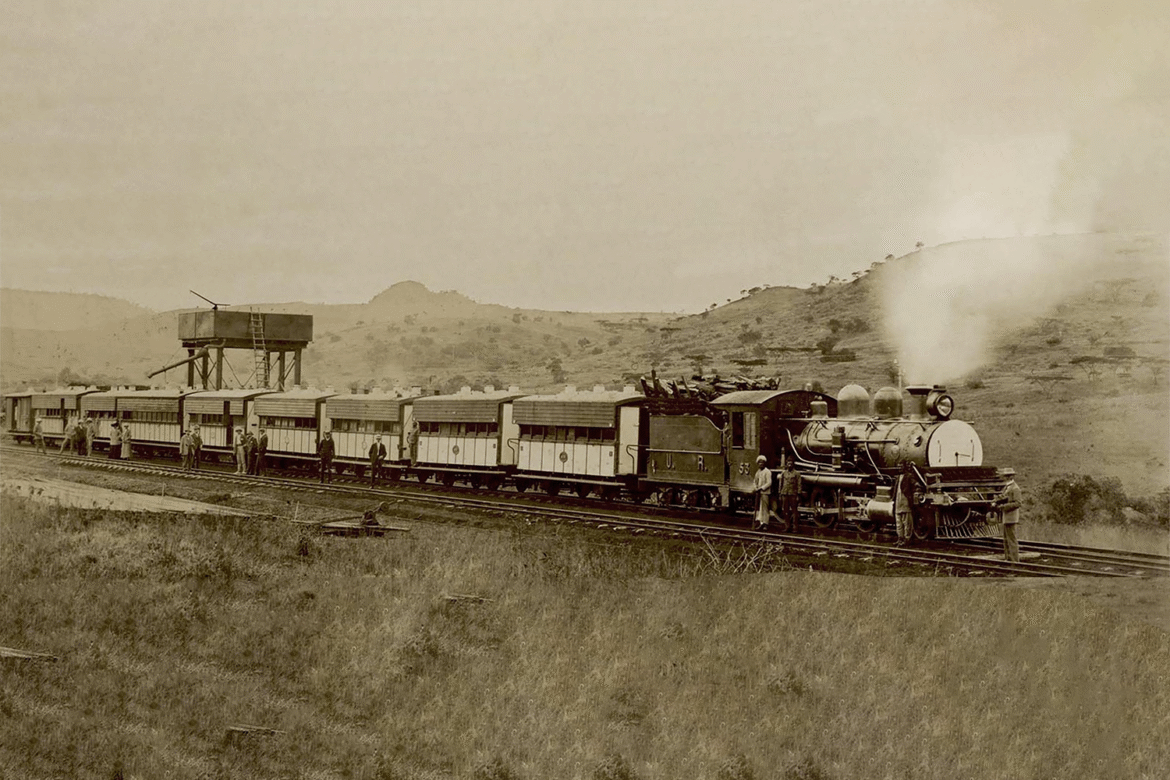

The Kenya–Uganda Railway, sometimes referred to historically as the “Lunatic Express,” remains one of East Africa’s most iconic and transformative infrastructure projects. Built at the close of the 19th century, the railway was originally designed to link the interior of Uganda to the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa, facilitating trade, governance, and the expansion of British colonial interests. More than a century later, it continues to shape the economic and political landscape of Kenya and Uganda.

Colonial Beginnings

Construction of the railway began in 1896, funded by the British government. The line was envisioned as a strategic artery to secure British control over Uganda and safeguard the upper Nile against rival colonial powers.

However, the project quickly gained notoriety. Its enormous cost, coupled with the challenges of building through swamps, escarpments, and wildlife-infested terrain, earned it the nickname the “Lunatic Line” in the British press. Engineers and workers contended with tropical diseases, hostile terrain, and, most infamously, man-eating lions that attacked railway camps near Tsavo.

Despite the hardships, the line reached Kisumu (then Port Florence) on Lake Victoria in 1901, effectively connecting the lake to the Indian Ocean.

Economic and Social Impact

The railway transformed the region.

-

Trade and Commerce: It opened up East Africa’s interior to global markets, allowing the export of coffee, tea, cotton, and other cash crops.

-

Urbanization: Key towns such as Nairobi—originally a railway depot—grew into major cities. Nairobi eventually became the capital of Kenya.

-

Migration: The project brought in thousands of Indian laborers, many of whom settled permanently in East Africa, giving rise to a significant South Asian community whose descendants still play vital roles in commerce today.

For Uganda, the line offered a reliable route for its exports, integrating the landlocked country more tightly into global trade networks.

Challenges and Decline

While revolutionary at the time, the metre-gauge railway faced neglect and underinvestment in the post-independence era. Aging tracks, inefficiency, and competition from road transport reduced its importance. By the early 21st century, freight volumes had plummeted, and much of the line had fallen into disrepair.

Modern Revivals: The Standard Gauge Railway (SGR)

To address these issues, Kenya launched the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) in 2017, financed largely by Chinese loans. The SGR links Mombasa to Nairobi, with plans to extend to Naivasha and eventually into Uganda, reviving the dream of a modern, seamless rail corridor across East Africa.

Uganda has expressed interest in connecting Kampala to the SGR network, though financing remains a key hurdle. If realized, the SGR could once again make rail the backbone of East African trade.

Symbolism and Legacy

The Kenya–Uganda Railway is more than steel and timber—it is a symbol of both colonial exploitation and regional transformation. It uprooted communities, altered migration patterns, and left a lasting imprint on East Africa’s economy and society. At the same time, it enabled growth, linked two nations, and laid the foundation for modern transport infrastructure.

✅ Takeaway: From its colonial roots to its modern reinvention, the Kenya–Uganda Railway tells the story of East Africa’s past and its ambitions for the future. What began as a controversial imperial project has evolved into a potential catalyst for regional integration and economic growth—proof that even “lunatic” visions can leave enduring legacies.

Last Updated on 6 months ago by %Sunday funday%